The Canadian Privacy Law Blog: Developments in privacy law and writings of a Canadian privacy lawyer, containing information related to the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (aka PIPEDA) and other Canadian and international laws.

Recent Posts

- Mining drivers' licence databases raises privacy c...

- US Federal Court limits police surveillance of pro...

- Taking care of business with the four Ps

- US DoD to require suppliers to use RFID

- Alberta Commissioner's office faults EAP provider

- Finding the smoking gun in security breaches

- Recruiting software company sets up data centre in...

- Call for a privacy law in Thailand

- OPC fact sheet on PIAs

- Federal Court orders Privacy Commissioner to inves...

On Twitter

About this page and the author

The author of this blog,

David T.S. Fraser, is a Canadian privacy lawyer who practices with the

firm of McInnes Cooper. He is the author of the Physicians' Privacy Manual. He has a national and international practice advising corporations and individuals on matters related to Canadian privacy laws.

The author of this blog,

David T.S. Fraser, is a Canadian privacy lawyer who practices with the

firm of McInnes Cooper. He is the author of the Physicians' Privacy Manual. He has a national and international practice advising corporations and individuals on matters related to Canadian privacy laws.

For full contact information and a brief bio, please see David's profile.

Please note that I am only able to provide legal advice to clients. I am not able to provide free legal advice. Any unsolicited information sent to David Fraser cannot be considered to be solicitor-client privileged.

Privacy Calendar

Archives

- January 2004

- February 2004

- March 2004

- April 2004

- May 2004

- June 2004

- July 2004

- August 2004

- September 2004

- October 2004

- November 2004

- December 2004

- January 2005

- February 2005

- March 2005

- April 2005

- May 2005

- June 2005

- July 2005

- August 2005

- September 2005

- October 2005

- November 2005

- December 2005

- January 2006

- February 2006

- March 2006

- April 2006

- May 2006

- June 2006

- July 2006

- August 2006

- September 2006

- October 2006

- November 2006

- December 2006

- January 2007

- February 2007

- March 2007

- April 2007

- May 2007

- June 2007

- July 2007

- August 2007

- September 2007

- October 2007

- November 2007

- December 2007

- January 2008

- February 2008

- March 2008

- April 2008

- May 2008

- June 2008

- July 2008

- August 2008

- September 2008

- October 2008

- November 2008

- December 2008

- January 2009

- February 2009

- March 2009

- April 2009

- May 2009

- June 2009

- July 2009

- August 2009

- September 2009

- October 2009

- November 2009

- December 2009

- January 2010

- February 2010

- March 2010

- April 2010

Links

Blogs I Follow

Small Print

The views expressed herein are solely the author's and should not be attributed to his employer or clients. Any postings on legal issues are provided as a public service, and do not constitute solicitation or provision of legal advice. The author makes no claims, promises or guarantees about the accuracy, completeness, or adequacy of the information contained herein or linked to. Nothing herein should be used as a substitute for the advice of competent counsel.

This web site is presented for informational purposes only. These materials do not constitute legal advice and do not create a solicitor-client relationship between you and David T.S. Fraser. If you are seeking specific advice related to Canadian privacy law or PIPEDA, contact the author, David T.S. Fraser.

Sunday, February 18, 2007

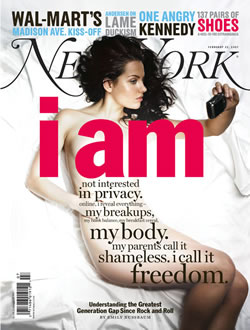

Kids, the Internet, and the End of Privacy: The Greatest Generation Gap Since Rock and Roll

Last night, I went to a party for a colleague celebrating her 36th birthday. The theme was pretty clever: to celebrate the tewentieth anniversary of her sweet sixteen. Guests were encouraged to wear their best '80s outfits. A number did and the outfits were classic. With MC Hammer blaring in the bar, there was some reminiscing about the teen years, twenty years ago.

Last night, I went to a party for a colleague celebrating her 36th birthday. The theme was pretty clever: to celebrate the tewentieth anniversary of her sweet sixteen. Guests were encouraged to wear their best '80s outfits. A number did and the outfits were classic. With MC Hammer blaring in the bar, there was some reminiscing about the teen years, twenty years ago. My generation is very different from those currently going through their teen years. I have to go down to the basement and open a trunk to find all the pictures that I took during those years. Many current teens just need to log into Myspace, Friendster, Flickr or pull up their blogs to find the full, detailed chronicle of their adolescence.

I'm a different person from who I was twenty years ago. I don't think I'd want to have that time of huge changes and wholesale weirdness on the 'net for all to see. (At the time I might have thought it was cool, but in retrospect .... not so much.)

Last week's New York magazine has a very interesting, feature length article on current teens and how their experiences are chronicled in great detail on the internet. Much of it deals with ADHD type attention spans and attention whoring, but the perception of privacy is very interesting.

Kids, the Internet, and the End of Privacy: The Greatest Generation Gap Since Rock and Roll -- New York MagazineKids today. They have no sense of shame. They have no sense of privacy. They are show-offs, fame whores, pornographic little loons who post their diaries, their phone numbers, their stupid poetry—for God’s sake, their dirty photos!—online. They have virtual friends instead of real ones. They talk in illiterate instant messages. They are interested only in attention—and yet they have zero attention span, flitting like hummingbirds from one virtual stage to another.

But maybe it’s a cheap shot to talk about reality television and Paris Hilton. Because what we’re discussing is something more radical if only because it is more ordinary: the fact that we are in the sticky center of a vast psychological experiment, one that’s only just begun to show results. More young people are putting more personal information out in public than any older person ever would—and yet they seem mysteriously healthy and normal, save for an entirely different definition of privacy. From their perspective, it’s the extreme caution of the earlier generation that’s the narcissistic thing. Or, as Kitty put it to me, “Why not? What’s the worst that’s going to happen? Twenty years down the road, someone’s gonna find your picture? Just make sure it’s a great picture.”

And after all, there is another way to look at this shift. Younger people, one could point out, are the only ones for whom it seems to have sunk in that the idea of a truly private life is already an illusion. Every street in New York has a surveillance camera. Each time you swipe your debit card at Duane Reade or use your MetroCard, that transaction is tracked. Your employer owns your e-mails. The NSA owns your phone calls. Your life is being lived in public whether you choose to acknowledge it or not.

So it may be time to consider the possibility that young people who behave as if privacy doesn’t exist are actually the sane people, not the insane ones. For someone like me, who grew up sealing my diary with a literal lock, this may be tough to accept. But under current circumstances, a defiant belief in holding things close to your chest might not be high-minded. It might be an artifact—quaint and naïve, like a determined faith that virginity keeps ladies pure. Or at least that might be true for someone who has grown up “putting themselves out there” and found that the benefits of being transparent make the risks worth it.

Labels: health information, privacy, surveillance

![]()

The Canadian Privacy Law Blog is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 2.5 Canada License.